Birds

A Bird Lover’s Paradise

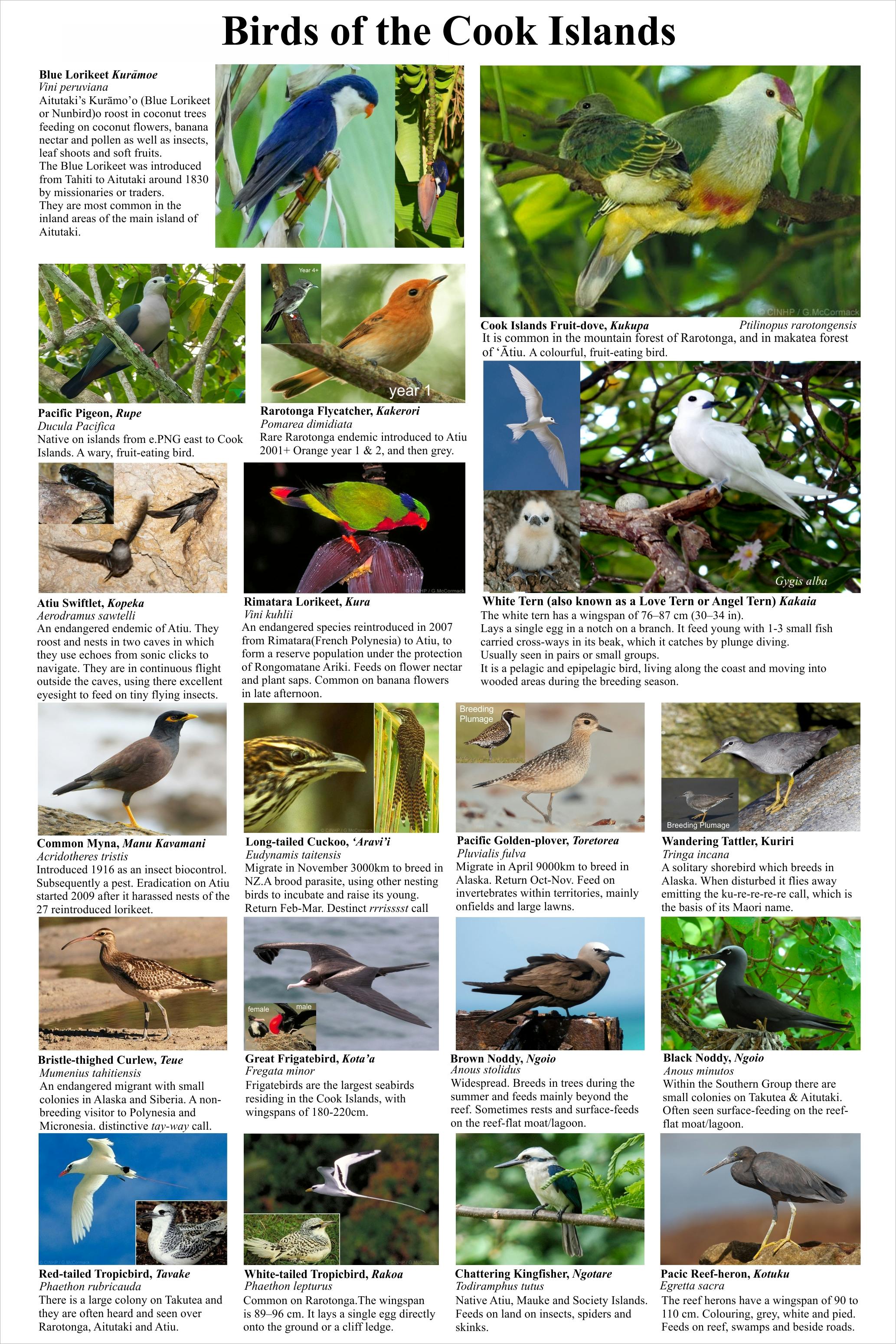

The Cook Islands offers bird lovers the chance to view some beautiful birdlife, including at least 6 which are only found here.

Birds hold deep significance in Polynesian traditions and are widely regarded throughout tropical Oceania as omens, signs, spirit helpers and spirit messengers.

Important Place in Cook Islands Culture

They had a vital place in traditional Cook Islands life. Birds provided feathers as markers of status and for adornment, such as the brilliant red feathers of the Kura or Rimatara Lorikeet, worn in their ears by the chiefs and women of Atiu (in the Southern Cook Islands) when Captain Cook visited in 1777, or the long, red streamer tail feathers of the elegant, slender Tavake or Red-Tailed Tropicbird which were highly prized throughout Polynesia.

Various birds were an important food source. The habits of birds were closely observed, and they became a rich source of metaphor and poetry. Their form was reflected in bird-shaped kites flown as a means of linking Earth to Heaven, and in deeply-meaningful tattoo patterns such as that of the Manutai, the seabird-shaped design modelled off the Kota’a orGreat Frigatebird’s distinctive silhouette with its massive chevron-shaped wing span and long forked tail.

Birds' behaviour was used to predict the weather, and sometimes the future.

Pointed the Way for Navigators

For early Polynesian navigators, migratory birds became wayfinders, their pathways pointing to the discovery of new lands. Ancestors of the New Zealand Māori are likely to have speculated that there had to be land in the south-west Pacific, as they observed the Aravi’i or Long-Tailed Cuckoo flying south from Rarotonga every spring and returning in autumn. Nowadays we know that to be a journey of 3,000 kilometres.

Rarotonga is Home to One of the World’s Rarest Birds

There are at least 8 threatened national land bird species found in the Cook Islands. Brought back from the brink of extinction is the unique Kakerori or Rarotonga Monarch Flycatcher (its name aptly describing its diet).

This delightful little bird, whose call sounds just like its Cook Islands Maori name, was still commonly seen throughout Rarotonga in the mid-1800s. By the early 1900s it was thought to have become extinct, until it was rediscovered living in dense bush in 1973.

In 1989 there were just 13 breeding pairs of Kakerori left, resulting in it being classified as Critically Endangered and being listed as one of the 10 rarest birds in the world. Through intensive conservation efforts such as rat control, the population has since been brought up to over 400 birds.

Visitors are able to enjoy guided tours through the lush valleys and highlands of the Takitumu Conservation Area where they can view the juvenile orange-coloured birds as well as older birds whose plumage has turned grey.

Rarotonga’s protected Takitumu Conservation Area is a 155 hectare (2.5% of Rarotonga’s land area) landowner community-managed forested area on the south-eastern side of Rarotonga, 7 minutes’ drive from The Rarotongan Beach Resort & Lagoonarium.

Kakerori are territorial birds favouring valleys sheltered from the prevailing south-east trade winds. Pairs remain in their territory for a year. Hens lay 1 to 2 eggs in nests positioned on forked branches, sometimes overhanging streams, and most eggs are laid in October and November.

Atiu – Island of the Birds

A second insurance population of Kakerori has also been successfully established through several translocations on another of the Southern Cooks Islands, Atiu, a raised-reef island known in Cook Islands Maori as Enua Manu, meaning “Island of the Birds”, where more than 200 Kakerori are now thriving.

The Kakerori is a symbol of hope of what concerted human conservation efforts can achieve. Without action, the Kakerori was expected to have become extinct by 2002.

Concerted conservation efforts have also led to the re-establishment of the vibrant red Kura or Rimatara Lorikeet. Once common on the island of Atiu in the Southern Cook Islands, this indigenous, colourful lorikeet was hunted to extinction there over 200 years ago (prior to the arrival of European settlers in the 1820s), but a population survived in the Austral Islands of French Polynesia and in 2007, 27 of these birds were gifted back to the Cook Islands where a healthy population has now been re-established on Atiu.

Atiu is a haven for birdwatchers with the widest variety of native land birds in the Cooks.

Found in only 2 Caves in the World

Its 6 indigenous resident land birds include the Kopeka or Atiu Swiftlet, unique to Atiu. This swiftlet is highly unusual in that it uses an audible clicking to navigate in the pitch-black interior of its breeding caves, a bit like a bat’s sonar. Atiu swiftlets are found in only 2 caves in the world, with a total of about 190 nests, and viewing tours are available on Atiu led by famous guide, Birdman George.

The Atiu Swiftlet, aptly named Aerodramus sawtelli, spends the majority of its life in flight. Highly aerodynamic, it has swept-back wings which resemble a boomerang, and perches only on vertical surfaces within its home cave.

Takutea Bird Sanctuary

Just off Atiu is the seabird island of Takutea, an uninhabited sand-cay of just over 1 square kilometre. Its traditional owners are the people of Atiu who have maintained Takutea as a wildlife sanctuary since early this century. It has the Cook Islands’ largest colony of Red-tailed Tropicbirds (1,500 pairs), and the only Southern Group colonies of Great Frigatebirds (100 pairs), Red-footed Boobies (100 pairs) and Brown Boobies (20 pairs). Takutea is also a regionally important wintering site for the Bristle-thighed Curlew, an Alaskan migrant listed as Vulnerable.

Southern Group

The Southern Group supports 11 indigenous, non-migratory landbirds. These include 4 single-island endemics (Rarotonga Monarch Flycatcher, Rarotonga Starling, Atiu Swiftlet and Tanga’eo the Mangaia Kingfisher) and 2 two-island endemics (Kukupa, the Cook Islands Fruit-Dove (Rarotonga and Atiu) and Kerearako, the Cook Islands Reed-Warbler (Mangaia and Mitiaro), listed as either Vulnerable or Critically Endangered. There are also 7 multi-island non-endemics (Grey Duck, Reef-Heron, Rupe the Pacific Fruit-Pigeon, Spotless Crake and Ngotare the Chattering Kingfisher). Only 3 introduced landbirds have naturalised: Red Junglefowl, Common Myna (which was introduced to control the coconut stick insect at the time of copra production, and has since become a pest) and the beautiful Blue Lorikeet.

Cook Islands Bird of the Year 2021

The Kuramo’oor Blue Lorikeet is a resident land-bird of special international interest. Endemic to neighbouring French Polynesia, its indigenous range decreased from more than 20 islands at the turn of the century to less than half that today, due to such threats as rats and cyclones.

The Blue Lorikeet was believed to have been brought to Aitutaki from French Polynesia as a caged bird in missionary times, probably as a chiefly gift. By 1899 it was referred to as a ‘pet of the natives’ and may have been regularly brought over as a cage bird on the many sailing ships from French Polynesia. Also called the Aitutaki Nunbird (or in French, Lori Nonnette, due to its blue nun’s habit appearance), it has since naturalized and thrived on Aitutaki, and in 2021 this charming little lori was crowned the Cook Islands Bird of the Year.

2nd and 3rd Place Getters

Voted in 2nd place was the 'I'oi or Rarotonga Starling which gets its name from its distinctive cheerful call, ‘’ee-oi, ee-oi!”, with each bird occupying a large area of territory within Rarotonga’s rugged interior.

William Wyatt-Gill, a missionary in the 1800s, wrote about the I`oi when he was in Rarotonga, and described hunting methods for catching flocks as they fed. A further challenge came when Myna birds were introduced to the island at the turn of the century as a means of biocontrol, thus driving indigenous birds to the highlands. Today I`oi are largely found in the highlands, although they still make the occasional appearance in gardens at lower levels. Classified as Vulnerable, the Rarotonga Starling is being closely monitored to ensure it does not become endangered.

Coming in 3rd place in the 2021 Cook Islands Bird of the Year was the Mōa Kirikiri (Pacific Fruit Bat). Of course, being a bat the Pacific Fruit Bat is not a bird as such, but it is the only native land mammal in the Cook Islands, and found only on Rarotonga and Mangaia, so holds a special place.

Suwarrow National Park

The southern-most island of the Northern Cooks, Suwarrow, is one of the most important sea-bird breeding areas in the South Pacific. This uninhabited atoll has been a national park since 1978. Its reef-islets, a mere 1.6km², support regionally significant colonies of Sooty Terns (100,000 pairs), Lesser Frigatebirds (5,000 pairs), Red-footed Boobies (1,000 pairs), Red-tailed Tropicbirds (500 pairs), and locally significant colonies of Great Frigatebirds (200 pairs), Brown Boobies (100 pairs) and Masked Boobies (10 pairs).

Most visitors to the Cook Islands are unlikely to make it as far as Suwarrow, however there are nevertheless a variety of birdwatching opportunities available on Rarotonga, Atiu and Aitutaki.

Birdwatching on Rarotonga

Where in other parts of the world some of the most common birds are likely to be sparrows, seagulls and pigeons, in the Cook Islands one of the most common birds visitors are likely to see, and definitely hear, is the introduced Red junglefowl. Handsome wild roosters and comely chickens are common all around Rarotonga’s lowland areas, and have even been seen high in the mountains by hikers making the Cross-Island Trek.

Along the shore from The Rarotongan guests can view Kotuku or Pacific Reef-Herons and Oystercatchers feeding in the shallows and Ngoio or Brown Noddies either flying out to sea at sunrise or returning at dusk from a day’s fishing.

Love Terns

A special treat is to see Kakaia or Love Terns (also called White or Angel Terns), usually in pairs, making wide graceful swoops and loops above the waters of Aroa Lagoonarium in front of both The Rarotongan and adults-only sister resort, Sanctuary Rarotonga-on the beach. With their pure white plumage set off with jet-black eyes and slim black beaks combined with a light aerodynamic frame and sheer grace in the skies, these are one of the world’s most beautiful seabirds, the closest one is likely to see angels in the sky.

Unusually, Love Terns do not construct a nest, instead choosing a suitable notch in a high branch of trees such as the Toa or Ironwood (Casuarina) tree to lay one egg. Terns are generally long-lived birds, with several species known to live in excess of 30 years.

The Great Migration of the Pacific Golden Plover

As you travel around Rarotonga and pass the end of the airport runway along the coastal road, look out for the pretty Kuriri or Pacific Golden Plover which returns from its breeding grounds in the Arctic tundra lands of western Alaska or Siberia to the same spot on Rarotonga each year. It migrates south during August and September and stays on Rarotonga until around April. Widely dispersed around the Pacific it is variously known as Torea, Toretorea, Kolea or Kuriri.

On Rarotonga, moult to breeding plumage begins around March, shortly prior to migration.

Although a shorebird, the Toretorea or Kuriri feeds mostly inland, preferring open spaces with short vegetation, such as the mown grass of the end of the Rarotonga Airport runway where it forages in a run-stop-peck pattern on insects, small reptiles, leaves and seeds.

Toretorea or Kuriri have adapted remarkably well to human presence and to human alteration of the natural environment making their territories in backyards, parks, cemeteries, rooftops, pastures, golf courses and the end of airport runways. Because they are site-faithful, each bird returns to and defends the same territory year after year, resulting in people being able to closely observe their comings and goings with special interest, some even naming and feeding the birds. The oldest Toretorea or Kuriri recorded lived to be over 21 years old.

Pacific Golden Plovers often gather in flocks some days prior to migrating north, and fly at altitudes of 3,000 feet (about 1 km) to as high as 16,000 feet (4.88 km). Some birds do not migrate. These are usually first-year, older or injured individuals, or birds without enough fat reserves to make the journey.

Scientists in Hawaiʻi attached tiny light-level geolocator devices to the birds and tracked them making the 3,000 mile (4,800 km) nonstop flight between Hawaiʻi and Alaska in 3-4 days.

Males usually arrive to their breeding grounds first, likely returning to, and defending, the same territory each year. The male builds a nest of lichen, moss, and grasses, in shallow scrapes of dry open area. The female lays 4 eggs, buff-coloured with splotches of black and brown. Male and female share incubation, care of young, and defence from foxes and avian predators.

Soon after hatching, chicks leave the nest to forage, returning to the parent birds to seek warmth and shelter. When juveniles are capable of flight around 26-28 days after hatching, parent birds begin to leave to migrate south to their territories such as those on Rarotonga.

Females usually depart first. Flocks of juveniles remain, making the migration sometimes as late as October and November depending on Arctic weather. First year birds migrate by instinct, confronting the vagaries of weather during their long southward flights. Once landed, they must compete with each other and established adults for foraging ground.

Although there are still healthy populations of Pacific Golden Plovers, the population trend is decreasing, the main threats being a global shift in the availability of habitat and an increase in severe weather events due to climate change.

The majestic Great Frigatebird

The end of Rarotonga Airport is a spot where you can also sometimes view another bird, the Kota’a or Great Frigatebird. Normally not seen near land except for when they seek shelter from storms out at sea, several of these majestic birds can be seen gliding on warm funnel-shaped currents above the end of the airport, sometimes building to as many as 20 or more individuals. Also known as Storm Birds, the males have bright red inflatable throat pouches.

Kota’a do not swim or walk and cannot take off from a flat surface. Having the largest wingspan-to-body-weight ratio of any bird, Great Frigatebirds are essentially aerial, able to stay aloft for more than a week. Frigate birds fly up to 100 km from land, petrels 70 km, and terns up to 50 km.

BACKGROUND

The Cook Islands consist of 15 islands scattered over some 2 million square kilometres of the Pacific Ocean, the size of Western Europe. They lie in the centre of the Polynesian Triangle, flanked to the west by the Kingdom of Tonga and the Samoas and to the east by Tahiti and the islands of French Polynesia.

The 15 islands divide socially and physically into the Northern Group of 6 islands and the Southern Group of 9 islands.

The Southern Group, with 90% of the land and 90% of the population, is physically diverse with a young volcanic island (Rarotonga), four raised-reef islands (Mangaia, Atiu, Mauke and Mitiaro), an almost-atoll (Aitutaki), two atolls (Manuae and Palmerston) and a sand-cay (Takutea). The hub of the Cook Islands, Rarotonga, is the largest (67km²), highest (653m) and most populated (8,000) island. The mountainous interior is tropical jungle and cloudforest supports 3 endemic landbirds.

Mangaia Kingfisher

Another special location for twitchers is the Southern Group island of Mangaia.

Mangaia, nearly the same size as Rarotonga, has eroded volcanic hills in the centre surrounded by a kilometre-wide limestone palisade – a raised-reef – reaching 60m elevation and supporting a healthy tropical forest. The fossil record shows that Mangaia had 13 resident landbirds, of which only 5 have survived, including the Tanga’eo or Mangaia Kingfisher, a single-island endemic.

During the early 1980s, residents of Mangaia were reporting that their kingfisher was declining in numbers, and they blamed the Common Myna, introduced around 1960. From the 149 kingfishers seen/heard, the estimated population was between 250 and 450 birds. It was concluded that the kingfishers bred more successfully in the dense Barringtonia patch-forests, and less successfully in open modified-forests where they were disturbed by the Myna.

Tool Use

Another bird of interest to keen birdwatchers is the migratory shorebird Teue or Bristle-thighed Curlew which uniquely among shorebirds becomes flightless during moult, making it vulnerable to predation from rats, cats and dogs.

In the Cook Islands, Bristle-thighed Curlews are found on the bird sanctuary island of Takutea just off Atiu and on Tongareva (Penryhn atoll), and have been recorded making non-stop flights in excess of 6,000 km.

Bristle-thighed curlews breed in two separate tundra areas in western Alaska, the Seward Peninsula and the Nulato Hills, Yukon delta, and migrate to spend the non-breeding season in the Pacific.

It is the only shorebird observed to use tools, breaking open other seabird eggs with stones to feed.

It was first described scientifically during Captain James Cook's visits to Tahiti in the 18th century, but its nesting grounds were not identified until 1948.

Survive and Thrive

Total bird species numbers in the Cook Islands have been variously listed as between 52-88, depending on how you count them, with between 8 to 13 considered to be threatened.

The present indigenous land birds of the Cook Islands are those that survived the two massive environmental upheavals: the arrival of the Polynesians about 2,000 years ago, and the arrival of Europeans since the 1820s.

Clearing of land for agriculture and building, use and overuse of chemicals, and introduced species such as cats, rats and Myna birds, all continue to pose significant challenges to the survival of the birds of the Cook Islands.

Conservation efforts are continuing to ensure that populations of threatened bird species do not die out but instead survive and thrive.

Learn more about our native species with the Cook Islands Natural Heritage Trusthttps://cinature.org/#gsc.tab=0

References include:

https://fatbirder.com/world-birding/australasia-or-oceania/cook-islands/

https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?region=CK&list=howardmoore

https://www.oneearth.org/ecoregions/cook-islands-tropical-moist-forests/

CLICK HERE to view the Cook Islands Biodiversity and Ethnobiology website